DENA DALE CRAIN

|

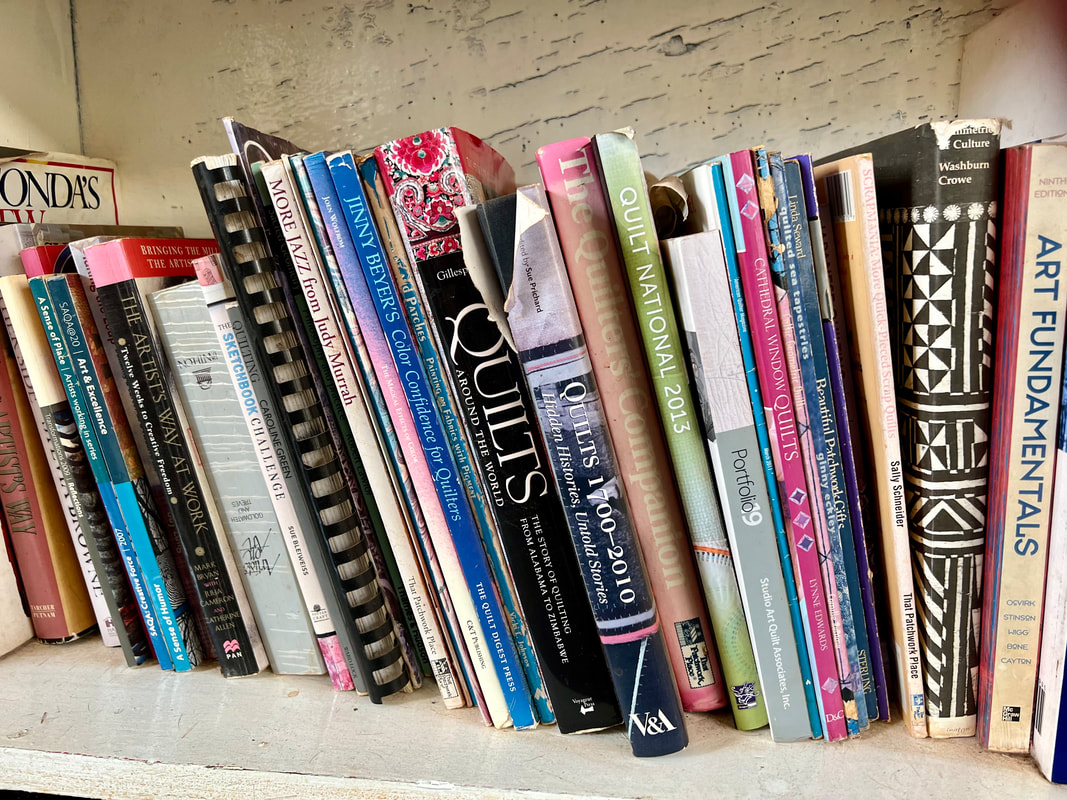

So, in typical fashion, everything has happened as it should have. I'm now ensconced in the house that was once my parents' home in Kentucky--my old Kentucky home! The first few days were expectedly rough, with only a mattress on the floor and a few borrowed kitchen items to get me started. My back is a high priority, so the mattress was my first purchase, but since then, I've sourced a loveseat and chair set, an end table, a couple of lamps, a decorative and warm bedcover, and a night table. To accomplish all this in 12 days has been a rush, but now I can begin to live more comfortably and get back to my prime directive: teaching quilters how to design! You can see above that my quilts are in temporary storage! The one on top is the piece I've been working on for many years, still unfinished after so many life journeys, and the one on the bottom is my baby quilt. There are others (my favs) inside this roll. To furnish my home, I've shopped at local furniture stores. (They all seem to be part of huge chains of shops; when did that happen?) Since then, I've been shopping at St. Vincent de Paul thrift stores to augment and balance the budget for those few expensive items I acquired. Best thing I ever did! I've just about stocked my kitchen hardware for a pittance, and everything I bought was in fantastic condition--like new! I even got a butcher-block knife stand, brand-new, still in the box, for $20, and that's half the price quoted online for it anywhere! Seeing all the good, often utterly unused, stuff you can find if you look for it is amazing! Now, though, I desperately need a dining room table and four chairs. I'll keep looking at the thrift shops and on FB. Thinking about furnishings, I've come up with an idea for a new lecture: "Clean Up Your Act." I need photographs that show messy studios and copyright permission to use those photos in my lectures. Will you send me a photo of your sewing space? If so, please use the contact form to tell me, and I'll send you instructions. And please hurry--I'm eager to get this lecture compiled and posted on my site. Thanks!

0 Comments

Throughout the last few years of my life, I've had to confront a truth that has not been entirely comfortable for me to embrace: the Universe is in charge!

I use the term "Universe" because mentioning any living or imaginary entity has become contentious. The last thing I want to do is to offend anyone by mentioning any deity they do not recognize affectionately. I also like the word "Universe" because it is not gender-specific but omnipresent, universal, and oddly comforting. What I've learned is that the Universe is in charge of everything. The best way to live, and possibly to die, is to welcome the Universe into our hearts and daily lives, allowing it to control whatever happens, even as we focus on the acceptance, gratitude, and peace of knowing that all will be well. "Sonny Patel" put it well in the movie, "The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel:" "In India, we have a saying: 'Everything will be alright in the end.' So if it is not alright, it is not yet the end." If it is not alright, be patient and wait. Things always change, and as change arrives, you will see then why you have been waiting. If you undertake any new objective and feel it is unnecessarily difficult to accomplish the task or achieve the goal, you probably should not be engaged in that activity. Stop and try something else. If the other thing you try works easily, that is what you were meant to do. If it does not go easily, try something else. Eventually, you will slip into some activity that is successful and immensely rewarding. The Universe tells us that sometimes, it is time to wait. When you feel there's nothing you can do without a huge struggle, don't even try. Wait and see what comes along without much effort on your part. That is probably what you are meant to do and will do successfully. I can hear you! You're saying even now, "Oh, but that flies in the face of everything I've ever been taught about accepting challenges and never giving up. How will I accomplish my goals if I give up on my projects?" See how "me"-focused are these remarks? Trust me, learning to relax and let the Universe look after you is far more productive than spinning your wheels, wasting resources and time, and becoming dispirited and disappointed over your "failures." Let me share with you a simple instance of how the Universe works: Yesterday, a good friend mentioned being interested in the Cincinnati Art Museum's "See the Story Book Club," a program offering a combination book club meeting to discuss a specific book with a fine arts tour to complement the book's subject. I heard her, but honestly, I didn't give the idea much thought. This morning, however, I received a subscription newsletter from CAM containing a reminder of the next book club meeting on September 16th. This meeting features the work of Amy Tan in "The Valley of Amazement." I like Amy Tan's work, but it's been a long time since I read anything by her. I went to my Libby app and checked to see if I could obtain the ebook with enough time to read it before September 16th. The app told me the book was available, but I would have to put a "hold" on it, and it would likely be two weeks before I could download a copy. I returned to the email and the CAM website to have a better look at what's available and coming up soon. Suddenly, I had a message on my phone. The book I had just requested was immediately available for download! Apparently, whoever had it before me chose that precise moment to return the book. I downloaded it, knowing that I'm now obliged to read the book and to attend the September 16th meeting at CAM. Would I have turned my back on the chance to download and read the book? Not for a minute! Why? Because I now know there's some important reason for me to attend that meeting on September 16th. It may or may not have anything at all to do with Amy Tan, but the Universe has sent me a signal, and I will do well to heed it. When good things fall into your lap unexpectedly, thank the Universe! When you fail miserably at a long-held goal, let it go. You're not meant to be doing that task, and while wasting time doing something you shouldn't, you will have missed out on how you should spend time and all the good things that will come from using time in synchronicity with the Universe. Please remember these ideas the next time you're stuck in traffic or waiting in a doctor's reception room. Find patience in the knowledge that everything happens for a reason, even if you cannot see what that reason is. Be aware when the Universe shifts the course of your life trajectory. Graciously and gratefully accept the change in plans. If you do, you will move happily with the Universe instead of always painfully swimming upstream. Before I left Kenya to return to the United States, there were tough choices to make. In 2020, when Jonny and I lost our home on the shore of Lake Baringo, we had been through a similar process. Flood waters rose so high that the bathroom plumbing wouldn't flush, and the kitchen sink drain wouldn't work either. My stepdaughter and I worked hard and fast to pack everything in the house and send it to Nairobi, either into the house where we would soon live or into more permanent storage. So, I was well prepared for my next life phase, saying goodbye to Kenya. A Marie Kondo fan, I had been working on downsizing for a while. Knowing that "You can't take it with you" made the process easier than it might have been. I gave away all my piano sheet music, painstakingly saved for over thirty years with no piano in sight, to a talented local musician, Michael James. Other pieces of the material culture of my life began to drift away as well. Soon, only my books and quilts were left. The books would stay. Finally, they went to the Kenya Quilt Guild, suffering badly after a flood damaged many of their library books stored by a third party. Initially, I thought of paying for excess baggage and bringing my quilts to the US, renting a public storage room, and plunking them there for safekeeping until I could find a way to sell them. However, research on storage facilities showed such an option was not advisable. Near desperation, I called my friend, Pat Jentz, the Kenya Museum Society Chairperson. She came to my home and looked at my quilts; then she left--thrilled--with a bundle of the worst ones! Ultimately, I set aside a precious few pieces I wanted to keep and donated the rest of my quilts to the Kenya Museum Society. I hoped the Society would sell the quilts fairly and use the funds for their projects. My logic was that during all the years of making the quilts, Jonny had supported me well, so that was my compensation for the work done. It seemed only right that any money raised by selling the quilts should go to the Nairobi National Museum, given that Jonny's parents and even himself were so much involved in establishing the Museum. Jonathan first curated the Nairobi Snake Park, and his parents, Louis and Mary, worked for the then Coryndon Museum. Now, I am delighted to tell you that my quilts are selling! I received a report from Karen Peachey, who oversees this effort, that seven quilts have sold and earned KES 300,000/-. The inventory of quilts was for about 70 pieces, so at this rate, they can earn the Museum Society as much as KES 3,000,000/-. In US dollars, that's over $21,000. That doesn't seem like much for over 20 years of work, but it will be a lot of money for the Museum Society to put to good work.

I can relax, knowing that the Universe is in charge, that my quilts will go to good homes with people who liked them well enough to pay for them, and that the Kenya Museum Society is the winner!

Did you ever come across a product that you thought was so cool, everyone should have one?

Well, on my housesit in South Philly, the homeowner had this gadget in her kitchen. At first, I couldn't figure out what it was, but it looked terribly useful. I'm sorry now that I didn't take a picture of it, but you'll get the idea: It was a cotton muslin bag about 6" deep, sewn onto a metal ring about 4 1/2" in diameter. The ends of the metal rod making the ring were inserted into a wooden handle. This simple kitchen gadget turned out to be a coffee maker! A heavy coffee drinker myself, wondering how I could carry a pound of coffee and a single-serving plunge pot in my limited carry-on baggage, I immediately appreciated the possibilities. Of course, I did the logical thing: I consulted Amazon! There, I did not find a cotton bag coffee maker like the one I'd seen, but I found this clever little thing (illustration shows two), lighter weight, more durable, and certainly cleaner (coffee somehow never comes out of cotton muslin) as it's dishwasher safe.

Not until I got to Charleston did I place the order, but having a cat chew my computer power cord put my business at risk. Needing to order a new cable, I tossed in the coffee maker as well (thus saving shipping charges), and I've been using it regularly ever since, made even easier by having a source of instant hot water in the home!

If you're a coffee drinker like me, and if you could even occasionally use a portable coffee maker, be sure to give this one a try! And please! Let me know how you like it in the comments below, thanks! Housesitting in Charleston, West Virginia, I visited the West Virginia State Museum yesterday. The Museum is remarkable and worth every effort to visit, tour, study, and enjoy--especially as admission is FREE! Seeing West Virginia's historical memorabilia on display was a particularly emotional experience for me. I'm an amateur genealogist, and my grandparents and beyond were from West Virginia, so many of the exhibits tugged at my heartstrings. More importantly, for our discussion here, my timing was excellent! Can you imagine my surprise to enter the building and be confronted by the West Virginia Quilters' annual quilt exhibition? The building is beautiful, and the entry hall is dramatic in its own right. The show was bold and dramatic because viewers could take in many quilts in one view. The colors and patterns fairly danced on the walls! The quilt display was impressive, especially for someone (like me) entering the hall for the first time. However, a close-up inspection of these beautiful quilts was impossible for obvious reasons. Certainly, the quilts were protected from well-meaning "touchers," people who do not know that excessive handling of quilts damages them. However, the quilts could not be viewed and appreciated close up in this venue. It was impossible to appreciate the fine detailing in design, not to mention the quality of the quilting stitches. The close-up shot below is not that; merely a blow-up of the image above. My advice before you go to see this show? Take your binoculars!

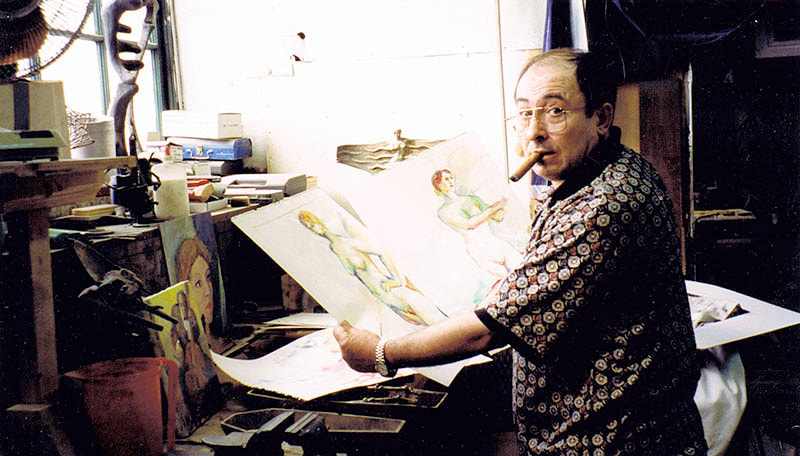

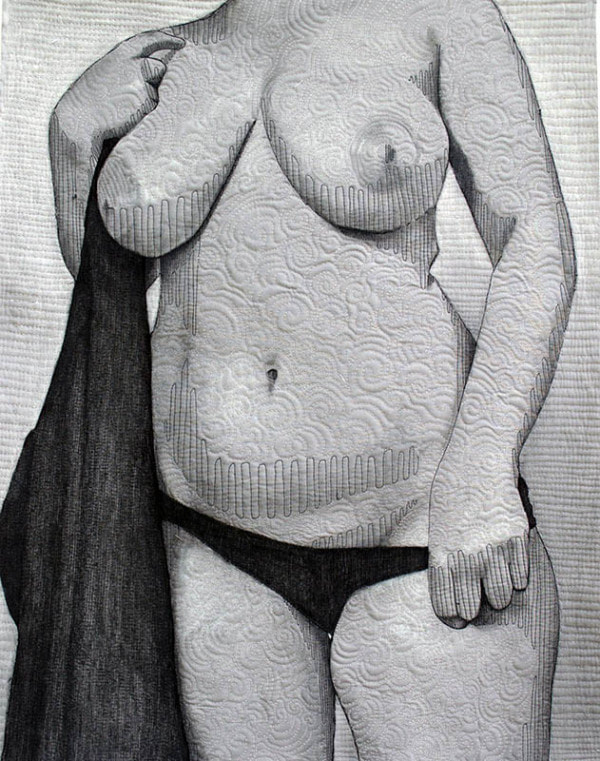

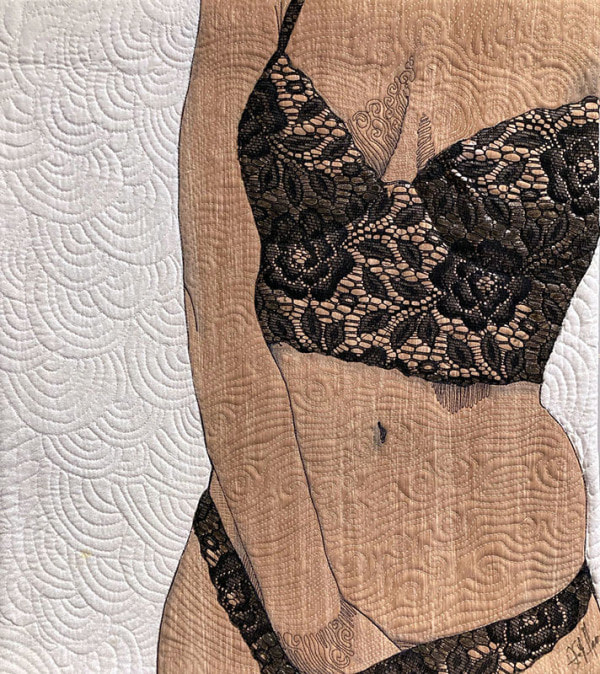

Find a list of the winners and awards here. It's unfortunate that the site fails to publish photos of the winning quilts. It would be good to see which quilts took awards and prizes. Surely, these fine, talented, and hard-working quilt-makers deserve the right to display their work proudly. Is the fear of copyright violation so paralyzing that no one shows anything anymore? The rek Gallery in Tucker, Georgia, held an opening yesterday evening for a showing of the works of Santos Fernandez. I attended the opening, which seemed popular amongst others in attendance. Although a small gallery, perhaps 40-50 people enjoyed the viewings and perhaps made a purchase during the brief time I was there. As a TrustedHousesitter visiting the area, I was favorably impressed by some of the work I saw. Vibrations of Picasso seemed present to my uneducated eye, but I loved the color palette present in much of Fernandez's work. In truth, it's a palette that seems special to this part of the country, one almost carelessly adding large areas of deeply toned blue, turquoise, purple, red, magenta, green, and orange, a little like a full-saturation color wheel with accents of tints and shades. Indeed, the home I am in as I write echoes those colors, boldly displayed so as to add richness and depth to the space, much as Fernandez' strokes relied on the same colors to move visual objects forward and backward on the imaginary plane. My sense of it is that Georgia celebrates color! However, there were other artists whose work was on display yesterday evening. Imagine my surprise when I realized one of them is a quilter! For several reasons, it was exciting to see the work of Jennifer Hart of Lexington, Kentucky. I was personally uncomfortable with the subject matter of Jennifer's work. Everything I saw was female in subject and virtually pornographic in approach. As an older woman, I am often dismayed to see the private parts of women used as subject matter for artworks, partly because doing so seems rather sensational, guaranteed to attract attention cheaply, and partly because I would like to think that some things are, and should remain, personal and special. Nevertheless, Hart's work was meticulously executed and fully acceptable, to my mind, as art. Her skill in crafts(wo)manship was high. Every stitch counted, and if there was an imperfection, my trained eye could not detect it. I especially appreciated learning about Hart's techniques. She works with colored pencils in most of her pieces, and she incorporates found objects like black lace in the most effective way. Hart's pieces are not large, seemingly no more than about 30" on the longest side, and many works were smaller than that. Because they are small and densely quilted, and because she turns the outermost edges in to leave a clean finish without a frame or telltale quilt binding, the pieces hang beautifully flat, so much so that at first glance, I did not realize they were quilts. Hart, I'm sure, and rightly, too, will argue that although craft is important, the content of her art takes priority. At least, that's what I discovered when I came across an article written by Katie Burkholder and published in February 2022 in The Georgia Voice. In the interview, Hart described a difficult and repressive childhood overcome by sheer force of will and determination. She is to be commended for her courage as well as her eye for meaningful content and intentional self-expression. My takeaway from last night's opening, in addition to the enjoyment of imagery, color, and form present in the work of Santos Fernandez, was an enhanced understanding of the way in which art quilts hanging amongst other media fit into the picture beautifully. One has to look closely to appreciate that Hart's quilts are quilts, and they easily cross the barrier from the world of handicrafts into the world of truly fine art. My compliments to the artist, Jennifer Hart! Oh--and if you want to see Hart's (and other artists') work up close and personal, better hurry! The gallery is about to go close its doors and go digital . . . Thinking again about Alison Sigethy's gorgeous Sea Cores exhibited in her gallery in the Torpedo Factory Art Center, let's talk about how best to capture such kinetic effects in patchwork quilting and why it is important to do so. The term "kinetic" refers to motion and the force and energy required to create it. The quilter's challenge is to incorporate a sense of motion when the materials we normally use present few opportunities to do that. However, as we see ourselves passing a mirror or any other reflective surface, we understand firsthand the phenomenon of motion. Psychology Today reports that it is important for us as human beings to see our own physical reflections. The report gives four solid reasons for this phenomenon as it urges us to take time to reflect upon ourselves:

Without detailing each of these four results of human interactivity, physical reflection gives patchwork quilt designers and makers a chance to incorporate movement into what would otherwise be a stable surface. Flashing lights, the movement of water or other substances, motion due to air currents: most of these and other such phenomena are not available to quilters due to technical difficulties. However, a single mirror, such as the one in the center of Bubbles III (encircled with two recycled glass rings), will catch and hold a passer-by's attention for several seconds. Possibly uncertain of the movement they saw while passing, viewers pause and focus on the quilt's center, seeking and finding their own reflection. Given enough time without disturbance, important glimpses of their faces in the quilt's center reward the viewers every time. Bubbles III is one of my most popular pieces. Generally speaking, any light-reflective surface will attract attention, even if it does not provide a specific image. There are many such reflective elements we can add to patchwork quilts:

These items can take many forms. Mirrors, for example, are available in various sizes and shapes, including circles, triangles, squares, and rectangles, and they can be sourced in a variety of sizes, even cut and shaped to our specifications. Sequins, beads, and crystals share light refraction from segmented surfaces. Basic light reflection without imagery occurs on any shiny metallic surface like that provided by metallic threads and paints, as well as many found objects. For my art piece, The Future is Now, a commissioned work produced for the Rockefeller Center offices in Kenya, I wanted to depict a stream of non-recyclable materials falling from the sky into the city of Nairobi. I used silver-colored silk and synthetic fabrics to define the landmark building towers of the downtown area. Then I embellished the quilt with recycled glass rings, sequins, glass and metal beads, a metallic mock-foil fabric, and even computer components! So, be creative in your use of reflective embellishments as you turn any patchwork quilt into a work of art. Seek unusual reflective objects that might be applied to a quilt and use them with careful thought to maximize the reflective effects. From Swarovski crystals to sea glass, from mirrors to metallic cords, from aluminum pop-top tabs to stainless steel kitchen implements, and from holographic ribbons to holiday foil wrappings, the list of reflective surface materials is long.

Keep purpose and safety uppermost in your mind, but experiment joyfully and thoroughly. After all, it's YOUR quilt! I visited the Torpedo Factory Art Center in Old Town Alexandria, Virginia, last week. Traveling solo, I got to see everything I wanted to see, and because it was a Friday, traffic in-house was light. Clearly, most of the artists do not spend all their time in their galleries/shops, which tells me they are still obliged to be making/selling art elsewhere. Some need equipment they cannot store in the TFAA. For example, hand-weaver Heasoon Rhee reported a need to work on a second, much larger, heavier, and noisier jacquard loom at home. Other TFAA artists go out to shop for supplies, visit corporate clients, or need a day off. Nevertheless, there were enough actively working artists present to make my visit there well worthwhile. Photos are not generally, for obvious reasons, permitted within the Torpedo Factory. Instead of photos, I share with you here the names and links of the artists whose work impressed me most, along with a brief comment about why I liked what they are doing: There’s an art jeweler in my family, so I’m accustomed to seeing and appreciating beautiful workmanship with carefully selected gemstones, but I found the addition of finely-worked cloisonné added much to the pieces produced by Holly Hague. There’s always a risk of looking overdone, that is, too much cloisonné for the gemstone, but Holly’s jewelry, I thought, balanced the stones and the art of enameling well. What do you think? (Comments welcome below.) Along similar lines was the work of weaver/glassworker Ruth Gowell. I found Ruth’s work stunning and reminiscent of a time when I hoped to work with the Kitengela Glass Factory many years ago to combine patchwork quilting and glass. The possibilities are, of course, endless, but Ruth’s work is a nearly perfect combination of the two media. It’s often hard to tell, in her Glass & Fiber Wall Art, where fiber leaves off and glass begins. Ruth does quite remarkable work—and her craftsmanship is impeccable! I was generally disappointed in the fiber arts section of the Torpedo Factory because it was so small! One relatively tiny gallery held the works of multiple fiber artists, each of whom should probably have their own space—economics at work, I suppose. I was pleased, however, to see the work of artists whose names I know, like Cindy Grisdela and Eileen Doughty (an old friend from SAQA), as well as the kawandi technique expressed by Linda Warschoff. Now, we’re talking MY language! Funny, though—my impression was that at least some work was underpriced; you should get it at these low prices while you can! Photographer Irina Rosovsky’s interior landscapes impressed me because I know those places intimately from my own Spirit Works. Her images depict foggy landscapes with forms barely recognizable. There’s a consistency to the work on display that revealed the artist’s search through her mind. As for paintings, there was a wide range of styles and media, as we might expect in such a venue, but one artist whose work really stood out for me was Mina Oka Hanig. Mina is painting patchwork—and it’s gorgeous! Art quilter and Juried Artist Member of SAQA, Katie Pasquini-Masopust (not part of the Torpedo Factory) does something similar, but her work is very different. Although Katie has a background in painting, she seems to come at the work more from the quilting side, whereas Mina’s work seems to flow from the painterly angle. For me, it’s interesting that both artists find their voices with paint and patches. Other artists at the Torpedo Factory whose work I want to mention as noteworthy to my way of thinking include: Lesley Clarke for encaustic as well as other paintings Sally Veach for paintings Guido R. Zanni for fluid acrylics (if you like this kind of thing) Cindy Lowther for tapestry and other hand weavings Carol Takov for interesting stone mosaics Last, but certainly not least, I want to mention the kinetic glass art of Alison Sigethy whose work has to be seen to be appreciated. Okay, I know it’s reminiscent of lava lamps, but Alison’s pieces have so much more to say. Kinetic work of any kind draws us in like a magnet, whether it’s good or bad, but these seemingly underwater scenes of delicate glass imagery offer much, much more. The rich colors and delicate structures of glass forms within each Sea Core are mesmerizing. The photos on these and other Torpedo Factory artists’ websites do not do the work justice. If you are in the D.C. area with a few hours of time on your hands, don’t miss seeing the art up close and personal. If you have space in your home or office and a bit of loose cash to spend, you can easily go home a proud owner of one of these amazing artists’ works. Special Tip from Dena:Give your patchwork quilts added painterly and kinetic qualities with these special artists' materials: acrylic fabric paint, glittering crystal beads, and shiny, light-reflective metallic threads.

New video on my YouTube channel: Rachel Derstine and the many words of wisdom she shared with me yesterday over coffee in her Philadelphia home and studio are much on my mind today. Rachel is not only a highly skilled teacher and a remarkable fine artist, but she is also generous and kind. She easily shares her experiences and what she has learned from them. We talked about the difficulties of selling patchwork quilts as works of art. Rachel recommended The Art Storefronts Organization and The Academy for Virtual Teaching, as well as Global Quilt Connection. I'm definitely interested and will be investigating these and other sites in coming days and weeks. If you know of any other useful resources for quilters selling art, please leave a comment below.

Find out more about Rachel from her website, https://www.rachelderstinedesigns.com. |

AboutMostly, I post on Facebook to tell you about my travels and life experiences, point out people and things that I want to tell you about, and keep you updated on what's happening in my life as an art quilter. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed